Showing posts with label jazz. Show all posts

Showing posts with label jazz. Show all posts

Saturday, January 19, 2013

365 Dry Martinis, my new blog.

I've done a little bit of jazz reviewing here on Dusty Slabs, but I've opened a new, jazz-only review blog called 365 Dry Martinis. Stop by and read short reviews of a different jazz album each day. They're each under 10 sentences, a form that I'm discovering is much harder to master than it sounds. If you're interested then please follow the link below, or you can find it in the sidebar at right. Have a nice day...

Sunday, December 30, 2012

Steely Dan / The Royal Scam (1976)

Royal Scam is like the middle child in the Steely Dan

discography, a precocious adolescent record that is somewhat awkward in

its nascence while offering tantalizing hints at the brilliance and

sophistication that became the band's hallmarks. I don't listen to it nearly as often as its immediate predecessor Katy Lied or masterful successor Aja, but each time I do, I remember what I'm missing. Those might be two of my favorite albums, but Scam is an underappreciated gem hiding in the shadows of its bigger brothers. I think it unfairly suffers for sounding, perhaps, too similar to Katy Lied while not quite achieving the same level creamy sophistication that was captured on Aja. Indeed, many of the songs would fit in nicely with the set on Katy Lied, and if you were so inclined, a seamless resequencing of the two records isn't a far fetched idea. But regardless of Scam's lack of further groundbreaking in terms of stylistic appeal, if you like Steely Dan, then you should find plenty to sink your teeth into. Scam has all the characteristics I attribute to Becker and Fagen's work.

As per usual, no two songs sound alike, and each one features a core group enhanced by a veteran session man. These contributions provide a variety of aural textures that buoy the program. Whether they are anchoring the rhythm section or setting the front line on fire, you can always expect fireworks from the sidemen on a Steely Dan LP. On almost every track, I really enjoy the Chuck Rainey's solid and soulful bass playing, for instance, and prominent work by guitarist Larry Carlton imparts a dazzling and sometimes grainy feel that was missing among the fold of Katy Lied. (The scholars among us will note that Carlton did the guitar bit on Katy Lied's "Daddy Don't Live in That New York City No More.") You'll also note the work of Steely stalwarts Denny Dias, playing the first solo in "Green Earrings" and Elliott Randall, who does the second. Becker steps out from behind the glass and gives the solo on "The Fez." And while he only gets a single solo spot, Paul Griffin plays piano on "Sign In Stranger," an ascerbic poke at musician union cronies. It's easily is my favorite track and possibly the best solo on the record.

Of course, it wouldn't be Steely Dan if the lyrics didn't tell great

stories (part fact, part fiction?) in entertaining and cryptic language

colored by great one-liners. Right out of the gate, Fagen spins sly

yarns about counterculture kingpins, the music business, coming of age,

and the plights of stupid young lovers, with more than a dash of wry

irony and humor. Musical styles bridge the territory between jazz, soul,

blues, pop, disco, and full-out rock and roll. I suppose that is what

the word "fusion" is for, but because it has acquired other connotations

that do not apply to Steely Dan, I want to steer away from it. If you're having trouble decoding some of the lyrics or want to fully appreciate the juicy imagery employed by Fagen, then stop by and have a look at the Steely Dan Dictionary. It's a user supported thing, so shoot them an email if you've got something to share. If that doesn't do it for you, then visit the Official Steely Dan Homepage FAQ -- which actually references the aforementioned SD Dictionary. I think you'll find the website is as entertaining as some of their liner notes. I've been listening to this record for a few hours now, and started my latest affair with it a few days ago. It's a rare thing when a record wears in to the equivocal point of a runner's high, providing more enjoyment on repeat listening, rather than less. There aren't many acts who can pull that off. As far as music goes, I love these guys. And I hope they don't ever stop.

Of course, it wouldn't be Steely Dan if the lyrics didn't tell great

stories (part fact, part fiction?) in entertaining and cryptic language

colored by great one-liners. Right out of the gate, Fagen spins sly

yarns about counterculture kingpins, the music business, coming of age,

and the plights of stupid young lovers, with more than a dash of wry

irony and humor. Musical styles bridge the territory between jazz, soul,

blues, pop, disco, and full-out rock and roll. I suppose that is what

the word "fusion" is for, but because it has acquired other connotations

that do not apply to Steely Dan, I want to steer away from it. If you're having trouble decoding some of the lyrics or want to fully appreciate the juicy imagery employed by Fagen, then stop by and have a look at the Steely Dan Dictionary. It's a user supported thing, so shoot them an email if you've got something to share. If that doesn't do it for you, then visit the Official Steely Dan Homepage FAQ -- which actually references the aforementioned SD Dictionary. I think you'll find the website is as entertaining as some of their liner notes. I've been listening to this record for a few hours now, and started my latest affair with it a few days ago. It's a rare thing when a record wears in to the equivocal point of a runner's high, providing more enjoyment on repeat listening, rather than less. There aren't many acts who can pull that off. As far as music goes, I love these guys. And I hope they don't ever stop.

As per usual, no two songs sound alike, and each one features a core group enhanced by a veteran session man. These contributions provide a variety of aural textures that buoy the program. Whether they are anchoring the rhythm section or setting the front line on fire, you can always expect fireworks from the sidemen on a Steely Dan LP. On almost every track, I really enjoy the Chuck Rainey's solid and soulful bass playing, for instance, and prominent work by guitarist Larry Carlton imparts a dazzling and sometimes grainy feel that was missing among the fold of Katy Lied. (The scholars among us will note that Carlton did the guitar bit on Katy Lied's "Daddy Don't Live in That New York City No More.") You'll also note the work of Steely stalwarts Denny Dias, playing the first solo in "Green Earrings" and Elliott Randall, who does the second. Becker steps out from behind the glass and gives the solo on "The Fez." And while he only gets a single solo spot, Paul Griffin plays piano on "Sign In Stranger," an ascerbic poke at musician union cronies. It's easily is my favorite track and possibly the best solo on the record.

Of course, it wouldn't be Steely Dan if the lyrics didn't tell great

stories (part fact, part fiction?) in entertaining and cryptic language

colored by great one-liners. Right out of the gate, Fagen spins sly

yarns about counterculture kingpins, the music business, coming of age,

and the plights of stupid young lovers, with more than a dash of wry

irony and humor. Musical styles bridge the territory between jazz, soul,

blues, pop, disco, and full-out rock and roll. I suppose that is what

the word "fusion" is for, but because it has acquired other connotations

that do not apply to Steely Dan, I want to steer away from it. If you're having trouble decoding some of the lyrics or want to fully appreciate the juicy imagery employed by Fagen, then stop by and have a look at the Steely Dan Dictionary. It's a user supported thing, so shoot them an email if you've got something to share. If that doesn't do it for you, then visit the Official Steely Dan Homepage FAQ -- which actually references the aforementioned SD Dictionary. I think you'll find the website is as entertaining as some of their liner notes. I've been listening to this record for a few hours now, and started my latest affair with it a few days ago. It's a rare thing when a record wears in to the equivocal point of a runner's high, providing more enjoyment on repeat listening, rather than less. There aren't many acts who can pull that off. As far as music goes, I love these guys. And I hope they don't ever stop.

Of course, it wouldn't be Steely Dan if the lyrics didn't tell great

stories (part fact, part fiction?) in entertaining and cryptic language

colored by great one-liners. Right out of the gate, Fagen spins sly

yarns about counterculture kingpins, the music business, coming of age,

and the plights of stupid young lovers, with more than a dash of wry

irony and humor. Musical styles bridge the territory between jazz, soul,

blues, pop, disco, and full-out rock and roll. I suppose that is what

the word "fusion" is for, but because it has acquired other connotations

that do not apply to Steely Dan, I want to steer away from it. If you're having trouble decoding some of the lyrics or want to fully appreciate the juicy imagery employed by Fagen, then stop by and have a look at the Steely Dan Dictionary. It's a user supported thing, so shoot them an email if you've got something to share. If that doesn't do it for you, then visit the Official Steely Dan Homepage FAQ -- which actually references the aforementioned SD Dictionary. I think you'll find the website is as entertaining as some of their liner notes. I've been listening to this record for a few hours now, and started my latest affair with it a few days ago. It's a rare thing when a record wears in to the equivocal point of a runner's high, providing more enjoyment on repeat listening, rather than less. There aren't many acts who can pull that off. As far as music goes, I love these guys. And I hope they don't ever stop.

Labels:

1976,

aja,

bear owsley stanley,

chuck rainey,

denny dias,

donald fagen,

elliott randall,

fusion,

jazz,

katy lied,

larry carlton,

paul griffin,

review,

rock,

soul,

steely dan,

the royal scam,

walter becker

Tuesday, September 11, 2012

Various Artists / Hittin' on All Six (2000)

This set covers the development of jazz guitar in the 20th century through the work of its most influential or innovative stylists. It is quite possibly the

best set of its kind, or at least the best one that I've come across. It explores the subject to an ideal depth, so the presentation is both informative and also enjoyable to listen to without losing focus or bogging down in unnecessary examples. Arranged chronologically, we hear selections from every crayon in the box, including both

lead and rhythm aces, from ragtime to bop. Thus each phase of jazz

guitar is illustrated in its proper context across three decades. There are

sides aplenty from big stars like Django, Lonnie Johnson and Charlie Christian, but you'll also find sides by lesser players like Tiny Grimes and Bus Etri. With so many highly skilled jazz guitarists working today, it’s easy

to take the guitar and its many historical innovators for granted. Here you have the best of the best, collected in one place. Incidentally, by covering the great bands, the program is also a good introduction to early jazz in general –

you get Bix, Bird, Duke, Basie, Louie, and others all in one place. Don't miss Eddie

Lang and Lonnie Johnson trading licks on “Have to Change Keys (To Play the

Blues),” just one rare delight of many.

Labels:

2000,

bix,

bus etri,

charlie parker,

count basie,

django reinhardt,

duke ellington,

early,

eddie lang,

guitar,

guitarist,

jazz,

lonnie johnson,

louis armstrong,

tiny grimes,

various artists

Joe Henderson / Power to the People (1969)

This isn’t the discordant, noisy

melee I expected from an album made during the earlier, exploratory phase of Joe Henderson’s career. It's fits in easily with other works of the new jazz being played in 1969 (Pharoah Sanders, Alice Coltrane, Miles Davis, etc.) but the seven originals are surprisingly chill compared

to Henderson’s work for the Blue Note label. On the opener “Black Narcissus,”

Henderson sketches out a haunting melody, showcasing its intrinsic beauty with

a reflective and provocative performance that recalls a tone poem. His voice on the tenor is unique and

expressive, working in matched phrases that intertwine with the ever searching and inventive electric piano by Herbie Hancock. Improvised sections are engaging and fun to listen to, especially the suite “Foresight and Afterthought.”

Therein, keep your ears peeled for a particularly gratifying eruption of emotive

force, a primal ejaculation of the blues, demonstrating that this group may be playing modern jazz but they

haven’t forgotten their roots. With Ron Carter on bass and Jack

DeJohnette on drums, it’s probably the best rhythm section to release an album

in 1969. The audio quality is superb, too, doing justice to each band member

equally. I frequently find myself in the car and panning the sound to the left channel to sit with Herbie and enjoy his licks in near-isolation.

Sunday, September 9, 2012

Ahmad Jamal Trio / Chamber Music of the New Jazz (1955)

With just a piano, guitar and bass, the lineup on this record is somewhat unconventional for a jazz piano trio, which usually consists of piano, bass, and drums. But Jamal has all the freedom he wants for interpretation, thus satisfying the purpose of playing with a trio instead of a larger group. At the same time, his work does not overshadow the proceedings to the point where other members cannot make contributions. Quite the contrary, all lights are equally bright here. The music, a combination of standards and originals by Jamal, is thoroughly enjoyable and the sound of the Argo CD is excellent. There is much eloquent phrasing from Jamal and Crawford on guitar. Jamal employs diverse techniques like walking colorfully voiced block chords, letting the left hand lay out, making playfully

creative runs with the right hand, and percussive forays into the dusty

end of the keyboard. Without a drummer he's also doing double duty with

Crosby, keeping time and adding lift with electric stabs at chords, a

bit like Duke would do. Crawford likes to alternate comping with delicious slides and arpeggiated runs or percussive plucking of the strings -- a technique later copied by scores of players. Israel Crosby, a great talent gone too soon from this Earth, provides almost supernatural rhythm with the bass and superb interplay with Jamal. The group chemistry is very positive so the recording stays fresh no matter how many times I've heard it. If you like Miles Davis then you'll want to pay special attention, because Miles was a big fan of Jamal's repertoire and arrangements. And so was Gil Evans, for that matter, who, you'll recall, is credited with arrangements on 'Miles Ahead' that were duly influenced by Mr. Jamal's trio. It doesn't matter if you're a seasoned jazz listener, are new to jazz, or don't care and just want something different to listen to: this recording is an essential.

Saturday, May 26, 2012

Joe Lovano Nonet / On This Day... Live at the Vanguard (2003)

I was blown away because

the sound of Lovano's nonet is HUGE! You feel the energy like you're

right there in the club. It's the only band I’ve ever heard that can

outstrip Mingus Big Band in terms of drive, presence or versatility. The

all-star lineup nails taut grooves like Lovano’s opener "At the

Vanguard" just as easily as they work the softer side of classic ballads

like "Laura" or “After the Rain.” The latter is a tasteful and well

executed cover of Coltrane’s moody, noir classic. It uniquely captures

all the longing and patiently developed beauty of the original, never

echoing Coltrane’s interpretation too closely. Moving to a tune that

Coltrane himself once covered, the band shifts gears with Tadd Dameron’s

“Good Bait” in a dangerously crowded and hard swinging arrangement that

gets the crowd roaring. In the middle, there’s a jumping solo from

baritone Scott Robinson that recalls the work of Gerry Mulligan but goes a few steps farther in its wild inventiveness. The

mark of a masterful improviser is that if you listen to the same solo

repeatedly, its spontaneity and spark will hold up each time, and it

will still surprise you. Soloing on this disc fits that bill. Everyone

shines, and it seems they all get a turn, too, punctuated by loud and

brassy figures blown by the whole group. Lovano is in top form, and so

is alto Steve Slagle. Somewhat hidden by the impressive reeds and brass, the rhythm section of John

Hicks and Lewis Nash offer the record’s hidden treasure. Nash’s

endlessly creative fills and sharp interjections of percussive voice

prod the arrangements with stimulating energy, while Hicks interplays

with soloists and comps reflectively on the piano. The album is in

regular rotation at my house, sometimes two or three times in a row.

Thanks, Joe.

Frank Zappa - Waka/Jawaka (1972)

Waka/Jawaka is the conceptual

follow-up to Hot Rats, the precocious middle child in the Hot Rats trilogy (Hot

Rats, Waka/Jawaka and The Grand Wazoo). Although Waka is very enjoyable by

itself, it’s a style in transition, a more complex offering that contains

beginnings of the big band sound later featured on the Grand Wazoo while

retaining only impressions of the hard rock grit from Hot Rats. The band, the structure of the compositions,

and the instrumentation are all in development. Overall, it is a much better

approximation of jazz-rock fusion than the heavy blues rock comprising most of the

Hot Rats set. “Your Mouth” features a dose of the sarcasm you’d expect from Zappa,

with a slinky melody and nice slide work by Tony Duran. But it’s the bookends

that really light things up. Opener “Big Swifty” and closer “Waka/Jawaka” are

two long jazz suites, a form that became Zappa’s favorite vehicle. These are

tightly arranged but have the loose feel of a rock band in full flight. There

are some awesome solos, too: Don Preston’s escapade on the Mini-Moog during

“Waka/Jawaka” is as notorious as it is entertaining: upon hearing it, inventor

Bob Moog supposedly remarked that such music was impossible on his instrument.

Zappa’s electric guitar colors the entire album, sounding more accomplished

here than on Hot Rats, always reminding listeners of the ‘rock’ half of the

‘jazz-rock’ recipe. It’s an enjoyable spin by itself, but is best heard in

context with the other albums in the trilogy. I recommend taking an afternoon

and listening to Hot Rats, Waka/Jawaka, and The Grand Wazoo, in that order.

When you’re finished, listen to all three again. Afterward, you’ll understand

what Zappa was cooking up. It isn’t pop music. It isn’t dance music or

background music or music for parties, like other music from 1972. It’s music

that rewards active listening because behind the fuzz bass and swirling

Mini-Moog, there are ideas. The Ryko CD release was doctored up a little bit

and sounds different than the original LP. In spite digital reverb applied to

the final production, it still sounds nice.

Labels:

big band,

big swifty,

conceptual continuity,

don preston,

electric guitar,

frank zappa,

fusion,

hot rats,

jazz,

review,

rock,

suite,

the grand wazoo,

tony duran,

trilogy,

waka/jawaka

Tuesday, May 22, 2012

Joe Lovano & Us Five / Folk Art (2009)

Every time I listen to Joe Lovano,

I’m thankful that he’s out there working. His performances and recordings are

consistently the most enjoyable in all of jazz, they are interesting in a musical way,

and of very high quality. Basically, they deliver. Folk Art is no exception.

In a feast for the ears, the Blue Note veteran and reedman extraordinaire here

pulls in a totally new band to record his first record comprised solely of

original material. As a guy who likes to interpret harmonies of Coltrane and

Coleman with the understanding that those guys were only interpreting

themselves, it’s nice to hear Lovano stretch out and, well, interpret Lovano. Of

course, the proceedings are hardly so simple, but that’s the direction. Right

from the outset, Lovano’s voice on the horn is typically sweeping, delicate and

reflective, although at times playful and mischievous. It’s a very deliberate

style, worked in concise lyrical phrases that spark with ingenuity and

curiosity. The compositions are a mixture of funky modern jazz

grooves, some with a quietly Latin feel. They oscillate between styles, touching on

soul jazz, blues, and the avant-garde. Plenty of room is given for the

band to stretch out and interact with each other. I

love the mood-changer “Song for Judi” with its ambling, pensive piano intro by

Weidman and sudden appearance of Lovano’s mysterioso tenor. Lost in the

beautiful melody, it surprises me every time I hear it. The track positively drips

with the influence of John Coltrane, as if he is hovering nearby in the

studio. I’ve noticed that in more than a

few of Lovano’s recordings, and I don’t think Lovano (or Coltrane) can

help the effect. Such channeling of one jazz spirit into another is the essence of harmony, and hearing it puts

goose bumps on my skin time after time. The band’s telepathic interplay and

remarkable chemistry is shown off in “Us Five,” a title which is actually the name of

the band. It allows relative newcomers like the brilliant bassist Esperanza

Spalding and drummers Otis Brown and Francisco Mela to move the melody as much

as Lovano does. Keeping with the loose theme suggested by the title, Lovano

enhances the sonic buffet by switching between straight alto, tenor, taragato,

autochrome, and alto clarinet numerous times. The textures swirl and influences

both past and present mingle in a jazz stew that respectfully embraces the laws

of the past, while pointing ever forward to new territory. Don't ever stop, Joe.

Labels:

album,

blue note,

esperanza spalding,

folk art,

francisco mela,

free jazz,

hard bop,

james weidman,

jazz,

joe lovano,

latin,

loft,

modern,

otis brown III,

quintet,

review,

us five

Sunday, April 22, 2012

Experiments in world fusion: Bill Frisell, Rabih Abou-Khalil, & Mahavishnu Orchestra

J.J. Johnson once remarked, "Jazz is restless. It won't stay put and it never will." It’s been this way since the beginning: the roots of jazz lay in a handful of musical traditions from Africa and Europe, as well as drawing on the blues, ragtime, and pop. Stylistic developments like bop, fusion, third stream, and soul jazz came about in a similar fashion, combining elements of other musics in the context of established jazz norms. World fusion, or cultural fusion, is a flexible subgenre that incorporates ethnic or non-Western musics into the construct of jazz music. It also works the other way around, and ethnic or non-Western musics which include jazz in their forays may be described by the term. If you like coffee, think of cultural fusion as a caffe americano or a long black. The ingredients are the same, hot water and espresso, but the order of their combination creates two entirely different beverages (although no one working at Starbucks seems to know the difference). Works of cultural fusion are no less stimulating than either of these drinks. If you’re looking to expand your listening horizons, try some of these exciting, genre bending titles.

A look at the lineup explains why The Intercontinentals is a good title. Leader and guitarist Bill Frisell, violinist Jenny Scheinman and multiinstrumentalist Greg Leisz bring their experience in American jazz and roots music. Also present are Malian guitarist and percussionist Sidikki Camara, Brazilian guitarist Vinicius Cantuaria, and Macedonian vocalist and oud player Christos Govetas. The melodies are smokey and mysterious, peppered by contributions of the players who reinvent the blues with improvisations of exciting texture and instrumentation. Listening feels like a midnight drive through an eerily familiar landscape and while you know the point of departure, the destination is uncertain. As the album meanders it stays accessible, deliciously soaked in reverb and governed by strong musicality. It relies on the players for its charm, but the focus is removed from any one solo voice and placed on group interplay, creating an interwoven tapestry that shimmers on the surface, unfolding to reveal new stylistic surprises.

Rabih Abou-Khalil – Bukra (1988)

Abou-Khalil is a Lebanese oud player whose work bridges the gap between American jazz, European classical, and traditional Arabic music. Teaming up with alto sax Sonny Fortune, bassist Glen Moore, and percussionists Ramesh Shotham and Glen Velez, Bukra departs immediately for new territories of cultural fusion. The opener “Fortune Seeker” inspires equally the hypnotic vision of a Bedouin caravan or dark nightclub. Don’t miss Fortune’s screaming, evocative introduction to “Kibbe,” or the sliding, pensive bass work by Moore on any track. Percussion plays a strong role in the course of each composition, but never dominates improvised sections. The album closes with some introspective and beautiful oud work by Abou-Khalil. The only downside to Bukra is that it ends too soon.

Mahavishnu Orchestra – Birds of Fire (1973)

After recording benchmark electric jazz-rock fusion with Miles Davis, John McLaughlin formed Mahavishnu Orchestra to bring his interests in jazz, funk, and Indian music to new heights. Birds of Fire is the second LP issued by the original lineup, and it best showcases the concepts the group was exploring. Furious energy, solos seamlessly divided between band members, and a melding of international influences in original compositions are the order of the day. Listen to “One Word” for the band’s ultimate statement, a 5-way musical argument of colliding meters and self-aggrandizing phrases. With this kind of energy, it’s no wonder the band broke up so soon. If Mahavishnu Orchestra was a bright star, then Birds of Fire was its supernova. A thing so brilliant simply couldn't last. If I had to pick, I'd take some of the later members of Mahavishnu over the players in this lineup, for instance, Stanley Clarke over Rick Laird (I know! Saying so is blasphemy). But it's a damned hard band to beat on any level, and one of the greatest lineups ever assembled for any type of music. It's no wonder that Birds of Fire became a crossover hit with rock audiences.

Saturday, February 4, 2012

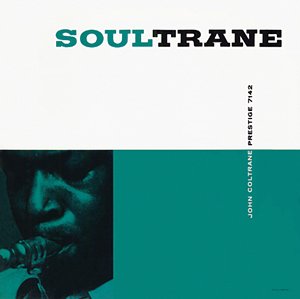

John Coltrane / Soultrane (1958)

Soultrane is just two sides long, a total of five cuts clocking in around 40 minutes, but it's pretty special. After first listening, critic Ira Gitler famously coined the term "sheets of sound" to describe Coltrane's wild new improvisational technique. That's a nice description, conjuring up cool imagery while defining in simple language what Coltrane was doing, which wasn't very simple at all. Or maybe it was devilishly simple? "Sheets of sound" refers to how Coltrane played hundreds of notes in a given solo at a lightning pace, creating dense aural textures that thrummed the ears like a raging waterfall. "His continuous flow of ideas without stopping really hit me," Gitler said. "It was almost superhuman. The amount of energy he was using could have powered a spaceship." That's wild language but it's hardly an overstatement. After you listen to Soultrane, compare what you hear to the other big tenors of 1958, and you'll immediately agree. It's a wonder the record doesn't fly right out the window.

I won't go into reviewing specific tracks, although the whole first side really shines, especially the opener, which is Tadd Dameron's "Good Bait." Instead, I'd like to say a few words about why I think the album is one that you need in your collection and why it stands as something of a watershed recording in jazz music.

John Coltrane was always an expressive soloist. Maybe it was his early days playing with the big-bellied alto of Earl Bostic that taught him to blow heavy soul through the horn. And his tenure under Miles Davis and Thelonious Monk certainly allowed Coltrane to explore the experimental side of his technique. But by 1958 he had found the formula to liberate his ideas from the bonds of harmonic theory based on chord progressions. It was an exciting time in jazz, and many young musicians were embracing modal techniques. Instead of waiting for a chord change to arrive and then playing a new selection of notes (much like a runner jumping hurdles), Coltrane piled the chord changes on top of one another within the moment the chord was played. This 'vertical' interpretation of harmony kicked open the door to a whole galaxy of tonal colors, making virtually anything possible - and correct - within the solo. Along with a sympathetic rhythm section, Coltrane now inflected his music with a special, new emotive quality and furious intensity. When I listen to Coltrane burn through a chorus, I close my eyes and see someone running madly through the halls of an art museum, arms outstretched, tagging the paintings on either wall before shooting out the door and collapsing on the steps.

One of my responsibilities as a librarian in the media department is to advise music listeners. After an advisory interview concerning jazz, I'll recommend Coltrane if it's relevant to what the patron is looking for. And interestingly, I've found that of the entire Coltrane canon, Soultrane has the distinction of being the album that most people who don't like Coltrane can actually enjoy. I've met more than a few jazz listeners who make a frightened face when I mention Trane or any of his records. Oh, how they love Zoot Sims and Hank Mobley! Nice boys. But somehow, the press succeeded in making people believe that you're either crazy or must enjoy differential calculus to enjoy John Coltrane. Nothing could be farther from the truth. After dishing Soultrane to skeptics, the same people often return and ask for more. Look at the credits and it's easier to understand what I mean: there are no Coltrane originals here, no weird intervals and arcane music theory. Instead you'll find standards from top to bottom, venerable tunes by the likes of Billy Eckstine, Tadd Dameron, Irving Berlin, played by the most competent quartet in the business. But you've never heard them like this.

The lineup is one of the most famous bands in jazz history. Coltrane, of course, leads on tenor with Red Garland on piano, Paul Chambers on bass, and Art Taylor on drums. Garland had a remarkable intuition for ensemble playing, and could build the mood like a tidal wave. The whole group was really quite telepathic in that sense, a seamlessly cohesive collaboration of creative genius and natural talent. By listening to the whole group interact, you feel Garland's effect which acts as a musical glue that binds the sound. Garland built on his band members' momentum and his initiative behind the piano controlled the rhythmic swell like he was working a throttle. Pay attention: after Coltrane finishes a chorus, you'll sense the band bumping into a higher gear. This is the difference between a good band and one that is merely competent. While soloing, Coltrane really gets out on a limb, pouring out successions of scales in breath length phrases. Garland is right there behind him, ever listening, interplaying with his own lines on the piano, so when Coltrane finishes, the band surges ahead with renewed urgency. But Garland is also a gifted soloist alternating between rich, soulful block chording and arpeggiated explosions of twinkling notes that shower listeners with an inexhaustible pallet of color. Paul Chambers is no slouch either, always fractions ahead of the beat, a guy who liked to cook. His deep tones are an audible heartbeat, the pulse of the group, and he moves like a phantom through the modal inclinations of his band members, adding to the mood and providing the backbone.

The lineup is one of the most famous bands in jazz history. Coltrane, of course, leads on tenor with Red Garland on piano, Paul Chambers on bass, and Art Taylor on drums. Garland had a remarkable intuition for ensemble playing, and could build the mood like a tidal wave. The whole group was really quite telepathic in that sense, a seamlessly cohesive collaboration of creative genius and natural talent. By listening to the whole group interact, you feel Garland's effect which acts as a musical glue that binds the sound. Garland built on his band members' momentum and his initiative behind the piano controlled the rhythmic swell like he was working a throttle. Pay attention: after Coltrane finishes a chorus, you'll sense the band bumping into a higher gear. This is the difference between a good band and one that is merely competent. While soloing, Coltrane really gets out on a limb, pouring out successions of scales in breath length phrases. Garland is right there behind him, ever listening, interplaying with his own lines on the piano, so when Coltrane finishes, the band surges ahead with renewed urgency. But Garland is also a gifted soloist alternating between rich, soulful block chording and arpeggiated explosions of twinkling notes that shower listeners with an inexhaustible pallet of color. Paul Chambers is no slouch either, always fractions ahead of the beat, a guy who liked to cook. His deep tones are an audible heartbeat, the pulse of the group, and he moves like a phantom through the modal inclinations of his band members, adding to the mood and providing the backbone.

It's an important album for a jazz listener to appreciate, but it's also just good fun to listen to and that's the important part. It's a record where everything seems to come together and make sense, and every time I listen feels like a special occasion. Take my word for it, try dropping the needle on Soultrane during your next Thanksgiving dinner.

I won't go into reviewing specific tracks, although the whole first side really shines, especially the opener, which is Tadd Dameron's "Good Bait." Instead, I'd like to say a few words about why I think the album is one that you need in your collection and why it stands as something of a watershed recording in jazz music.

John Coltrane was always an expressive soloist. Maybe it was his early days playing with the big-bellied alto of Earl Bostic that taught him to blow heavy soul through the horn. And his tenure under Miles Davis and Thelonious Monk certainly allowed Coltrane to explore the experimental side of his technique. But by 1958 he had found the formula to liberate his ideas from the bonds of harmonic theory based on chord progressions. It was an exciting time in jazz, and many young musicians were embracing modal techniques. Instead of waiting for a chord change to arrive and then playing a new selection of notes (much like a runner jumping hurdles), Coltrane piled the chord changes on top of one another within the moment the chord was played. This 'vertical' interpretation of harmony kicked open the door to a whole galaxy of tonal colors, making virtually anything possible - and correct - within the solo. Along with a sympathetic rhythm section, Coltrane now inflected his music with a special, new emotive quality and furious intensity. When I listen to Coltrane burn through a chorus, I close my eyes and see someone running madly through the halls of an art museum, arms outstretched, tagging the paintings on either wall before shooting out the door and collapsing on the steps.

One of my responsibilities as a librarian in the media department is to advise music listeners. After an advisory interview concerning jazz, I'll recommend Coltrane if it's relevant to what the patron is looking for. And interestingly, I've found that of the entire Coltrane canon, Soultrane has the distinction of being the album that most people who don't like Coltrane can actually enjoy. I've met more than a few jazz listeners who make a frightened face when I mention Trane or any of his records. Oh, how they love Zoot Sims and Hank Mobley! Nice boys. But somehow, the press succeeded in making people believe that you're either crazy or must enjoy differential calculus to enjoy John Coltrane. Nothing could be farther from the truth. After dishing Soultrane to skeptics, the same people often return and ask for more. Look at the credits and it's easier to understand what I mean: there are no Coltrane originals here, no weird intervals and arcane music theory. Instead you'll find standards from top to bottom, venerable tunes by the likes of Billy Eckstine, Tadd Dameron, Irving Berlin, played by the most competent quartet in the business. But you've never heard them like this.

The lineup is one of the most famous bands in jazz history. Coltrane, of course, leads on tenor with Red Garland on piano, Paul Chambers on bass, and Art Taylor on drums. Garland had a remarkable intuition for ensemble playing, and could build the mood like a tidal wave. The whole group was really quite telepathic in that sense, a seamlessly cohesive collaboration of creative genius and natural talent. By listening to the whole group interact, you feel Garland's effect which acts as a musical glue that binds the sound. Garland built on his band members' momentum and his initiative behind the piano controlled the rhythmic swell like he was working a throttle. Pay attention: after Coltrane finishes a chorus, you'll sense the band bumping into a higher gear. This is the difference between a good band and one that is merely competent. While soloing, Coltrane really gets out on a limb, pouring out successions of scales in breath length phrases. Garland is right there behind him, ever listening, interplaying with his own lines on the piano, so when Coltrane finishes, the band surges ahead with renewed urgency. But Garland is also a gifted soloist alternating between rich, soulful block chording and arpeggiated explosions of twinkling notes that shower listeners with an inexhaustible pallet of color. Paul Chambers is no slouch either, always fractions ahead of the beat, a guy who liked to cook. His deep tones are an audible heartbeat, the pulse of the group, and he moves like a phantom through the modal inclinations of his band members, adding to the mood and providing the backbone.

The lineup is one of the most famous bands in jazz history. Coltrane, of course, leads on tenor with Red Garland on piano, Paul Chambers on bass, and Art Taylor on drums. Garland had a remarkable intuition for ensemble playing, and could build the mood like a tidal wave. The whole group was really quite telepathic in that sense, a seamlessly cohesive collaboration of creative genius and natural talent. By listening to the whole group interact, you feel Garland's effect which acts as a musical glue that binds the sound. Garland built on his band members' momentum and his initiative behind the piano controlled the rhythmic swell like he was working a throttle. Pay attention: after Coltrane finishes a chorus, you'll sense the band bumping into a higher gear. This is the difference between a good band and one that is merely competent. While soloing, Coltrane really gets out on a limb, pouring out successions of scales in breath length phrases. Garland is right there behind him, ever listening, interplaying with his own lines on the piano, so when Coltrane finishes, the band surges ahead with renewed urgency. But Garland is also a gifted soloist alternating between rich, soulful block chording and arpeggiated explosions of twinkling notes that shower listeners with an inexhaustible pallet of color. Paul Chambers is no slouch either, always fractions ahead of the beat, a guy who liked to cook. His deep tones are an audible heartbeat, the pulse of the group, and he moves like a phantom through the modal inclinations of his band members, adding to the mood and providing the backbone. It's an important album for a jazz listener to appreciate, but it's also just good fun to listen to and that's the important part. It's a record where everything seems to come together and make sense, and every time I listen feels like a special occasion. Take my word for it, try dropping the needle on Soultrane during your next Thanksgiving dinner.

Labels:

art taylor,

earl bostic,

hard bop,

ira gitler,

jazz,

john coltrane,

miles davis,

modal,

paul chambers,

red garland,

review,

rudy van gelder,

sheets of sound,

soultrane,

thelonious monk

Wednesday, February 1, 2012

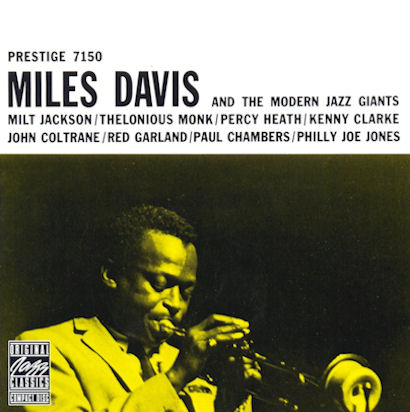

Miles Davis and the Modern Jazz Giants (1958)

Miles Davis and the Modern Jazz Giants is one of my favorite jazz albums. I'm a big fan of most Prestige releases but this one is especially enjoyable. It is positively brimming with musical excitement and high quality performances make it an easy candidate for repeat listening. The tracks are culled from a session recorded Christmas Eve, 1954 by the inimitable Rudy Van Gelder. It's an impressive roster by any measure: Milt Jackson on vibes, Percy Heath on bass, Thelonious Monk on piano, Kenny Clarke on drums and of course Miles playing the horn. "Round Midnight" is odd man out, recorded in 1956 by the same lineup heard on Steamin'. If you're at all familiar with the various groups led by Davis in the 1950s, then this misfit should stick out like a sore lip. The feel is completely different, and the personalities don't bounce off each other the same way. It's an awesome take, and any take with Coltrane is a bonus in my book, but it's obviously a different band and it just doesn't sound anything like the rest of the album.

The sheer chemistry is what jumps out at me most. There is tangible musical evidence of the friction caused by Monk working under Davis' direction. Monk didn't like being told to lay out during Miles' solos, and so when he takes one of his own, he really lets you know he's there. The result is a pleasing musical tension that spins topsy-turvy somewhere between mood and mechanics. There are few pianists who understand rhythm and dissonance like Monk, and his penchant for playing the perfectly wrong note in the perfectly right spot is maximized here. Phrases of Monk's sparse, single note solos hang across the bars, as if to be completed at a later date, creating time within time. Through such economy, the impact of his absence is even stronger and the tunes acquire a presence that is felt as much as heard. The album isn't all Monk, I just mention him because his work is notable. Really, if there's one standout star then it's Milt Jackson on the vibes. Jackson provides the fabric for the whole album, smoothing it over like sand filling in fault lines, providing both body and character. At times, his licks seem to intervene between Monk and Davis, and tie the arrangements together like string. Meanwhile, Clarke and Heath are a rock, their interplay with soloists and solid timekeeping during heads propelling the music in interesting new directions. Not to be forgotten, Miles' tone on the horn is characteristically creamy and his solos are filled with chilled out, mid-register phrases that smolder in their simplicity. By not flying up the scales or playing successive double-time runs, Davis maintains a consistent atmosphere that focuses his ideas and swells the music with controlled intensity. Hours after listening, the strains ring in my ears and I have to put it on again. It's almost addictive. Almost. If Kind of Blue was missing and I had to choose one album to serve as a new listener's introduction to jazz, this very well might be it. So do yourself a favor, hunt down a copy. The CD reissue by Original Jazz Classics is an excellent alternative to the original LP.

The sheer chemistry is what jumps out at me most. There is tangible musical evidence of the friction caused by Monk working under Davis' direction. Monk didn't like being told to lay out during Miles' solos, and so when he takes one of his own, he really lets you know he's there. The result is a pleasing musical tension that spins topsy-turvy somewhere between mood and mechanics. There are few pianists who understand rhythm and dissonance like Monk, and his penchant for playing the perfectly wrong note in the perfectly right spot is maximized here. Phrases of Monk's sparse, single note solos hang across the bars, as if to be completed at a later date, creating time within time. Through such economy, the impact of his absence is even stronger and the tunes acquire a presence that is felt as much as heard. The album isn't all Monk, I just mention him because his work is notable. Really, if there's one standout star then it's Milt Jackson on the vibes. Jackson provides the fabric for the whole album, smoothing it over like sand filling in fault lines, providing both body and character. At times, his licks seem to intervene between Monk and Davis, and tie the arrangements together like string. Meanwhile, Clarke and Heath are a rock, their interplay with soloists and solid timekeeping during heads propelling the music in interesting new directions. Not to be forgotten, Miles' tone on the horn is characteristically creamy and his solos are filled with chilled out, mid-register phrases that smolder in their simplicity. By not flying up the scales or playing successive double-time runs, Davis maintains a consistent atmosphere that focuses his ideas and swells the music with controlled intensity. Hours after listening, the strains ring in my ears and I have to put it on again. It's almost addictive. Almost. If Kind of Blue was missing and I had to choose one album to serve as a new listener's introduction to jazz, this very well might be it. So do yourself a favor, hunt down a copy. The CD reissue by Original Jazz Classics is an excellent alternative to the original LP.

The sheer chemistry is what jumps out at me most. There is tangible musical evidence of the friction caused by Monk working under Davis' direction. Monk didn't like being told to lay out during Miles' solos, and so when he takes one of his own, he really lets you know he's there. The result is a pleasing musical tension that spins topsy-turvy somewhere between mood and mechanics. There are few pianists who understand rhythm and dissonance like Monk, and his penchant for playing the perfectly wrong note in the perfectly right spot is maximized here. Phrases of Monk's sparse, single note solos hang across the bars, as if to be completed at a later date, creating time within time. Through such economy, the impact of his absence is even stronger and the tunes acquire a presence that is felt as much as heard. The album isn't all Monk, I just mention him because his work is notable. Really, if there's one standout star then it's Milt Jackson on the vibes. Jackson provides the fabric for the whole album, smoothing it over like sand filling in fault lines, providing both body and character. At times, his licks seem to intervene between Monk and Davis, and tie the arrangements together like string. Meanwhile, Clarke and Heath are a rock, their interplay with soloists and solid timekeeping during heads propelling the music in interesting new directions. Not to be forgotten, Miles' tone on the horn is characteristically creamy and his solos are filled with chilled out, mid-register phrases that smolder in their simplicity. By not flying up the scales or playing successive double-time runs, Davis maintains a consistent atmosphere that focuses his ideas and swells the music with controlled intensity. Hours after listening, the strains ring in my ears and I have to put it on again. It's almost addictive. Almost. If Kind of Blue was missing and I had to choose one album to serve as a new listener's introduction to jazz, this very well might be it. So do yourself a favor, hunt down a copy. The CD reissue by Original Jazz Classics is an excellent alternative to the original LP.

The sheer chemistry is what jumps out at me most. There is tangible musical evidence of the friction caused by Monk working under Davis' direction. Monk didn't like being told to lay out during Miles' solos, and so when he takes one of his own, he really lets you know he's there. The result is a pleasing musical tension that spins topsy-turvy somewhere between mood and mechanics. There are few pianists who understand rhythm and dissonance like Monk, and his penchant for playing the perfectly wrong note in the perfectly right spot is maximized here. Phrases of Monk's sparse, single note solos hang across the bars, as if to be completed at a later date, creating time within time. Through such economy, the impact of his absence is even stronger and the tunes acquire a presence that is felt as much as heard. The album isn't all Monk, I just mention him because his work is notable. Really, if there's one standout star then it's Milt Jackson on the vibes. Jackson provides the fabric for the whole album, smoothing it over like sand filling in fault lines, providing both body and character. At times, his licks seem to intervene between Monk and Davis, and tie the arrangements together like string. Meanwhile, Clarke and Heath are a rock, their interplay with soloists and solid timekeeping during heads propelling the music in interesting new directions. Not to be forgotten, Miles' tone on the horn is characteristically creamy and his solos are filled with chilled out, mid-register phrases that smolder in their simplicity. By not flying up the scales or playing successive double-time runs, Davis maintains a consistent atmosphere that focuses his ideas and swells the music with controlled intensity. Hours after listening, the strains ring in my ears and I have to put it on again. It's almost addictive. Almost. If Kind of Blue was missing and I had to choose one album to serve as a new listener's introduction to jazz, this very well might be it. So do yourself a favor, hunt down a copy. The CD reissue by Original Jazz Classics is an excellent alternative to the original LP.Curious? Want some more? Have a gander at MilesDavis.com

Impress your friends and purchase a Harmon trumpet mute.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)