I won't go into reviewing specific tracks, although the whole first side really shines, especially the opener, which is Tadd Dameron's "Good Bait." Instead, I'd like to say a few words about why I think the album is one that you need in your collection and why it stands as something of a watershed recording in jazz music.

John Coltrane was always an expressive soloist. Maybe it was his early days playing with the big-bellied alto of Earl Bostic that taught him to blow heavy soul through the horn. And his tenure under Miles Davis and Thelonious Monk certainly allowed Coltrane to explore the experimental side of his technique. But by 1958 he had found the formula to liberate his ideas from the bonds of harmonic theory based on chord progressions. It was an exciting time in jazz, and many young musicians were embracing modal techniques. Instead of waiting for a chord change to arrive and then playing a new selection of notes (much like a runner jumping hurdles), Coltrane piled the chord changes on top of one another within the moment the chord was played. This 'vertical' interpretation of harmony kicked open the door to a whole galaxy of tonal colors, making virtually anything possible - and correct - within the solo. Along with a sympathetic rhythm section, Coltrane now inflected his music with a special, new emotive quality and furious intensity. When I listen to Coltrane burn through a chorus, I close my eyes and see someone running madly through the halls of an art museum, arms outstretched, tagging the paintings on either wall before shooting out the door and collapsing on the steps.

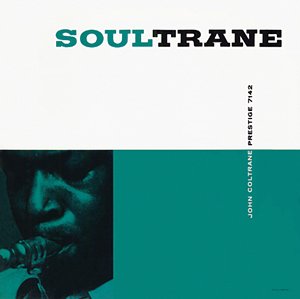

One of my responsibilities as a librarian in the media department is to advise music listeners. After an advisory interview concerning jazz, I'll recommend Coltrane if it's relevant to what the patron is looking for. And interestingly, I've found that of the entire Coltrane canon, Soultrane has the distinction of being the album that most people who don't like Coltrane can actually enjoy. I've met more than a few jazz listeners who make a frightened face when I mention Trane or any of his records. Oh, how they love Zoot Sims and Hank Mobley! Nice boys. But somehow, the press succeeded in making people believe that you're either crazy or must enjoy differential calculus to enjoy John Coltrane. Nothing could be farther from the truth. After dishing Soultrane to skeptics, the same people often return and ask for more. Look at the credits and it's easier to understand what I mean: there are no Coltrane originals here, no weird intervals and arcane music theory. Instead you'll find standards from top to bottom, venerable tunes by the likes of Billy Eckstine, Tadd Dameron, Irving Berlin, played by the most competent quartet in the business. But you've never heard them like this.

The lineup is one of the most famous bands in jazz history. Coltrane, of course, leads on tenor with Red Garland on piano, Paul Chambers on bass, and Art Taylor on drums. Garland had a remarkable intuition for ensemble playing, and could build the mood like a tidal wave. The whole group was really quite telepathic in that sense, a seamlessly cohesive collaboration of creative genius and natural talent. By listening to the whole group interact, you feel Garland's effect which acts as a musical glue that binds the sound. Garland built on his band members' momentum and his initiative behind the piano controlled the rhythmic swell like he was working a throttle. Pay attention: after Coltrane finishes a chorus, you'll sense the band bumping into a higher gear. This is the difference between a good band and one that is merely competent. While soloing, Coltrane really gets out on a limb, pouring out successions of scales in breath length phrases. Garland is right there behind him, ever listening, interplaying with his own lines on the piano, so when Coltrane finishes, the band surges ahead with renewed urgency. But Garland is also a gifted soloist alternating between rich, soulful block chording and arpeggiated explosions of twinkling notes that shower listeners with an inexhaustible pallet of color. Paul Chambers is no slouch either, always fractions ahead of the beat, a guy who liked to cook. His deep tones are an audible heartbeat, the pulse of the group, and he moves like a phantom through the modal inclinations of his band members, adding to the mood and providing the backbone.

The lineup is one of the most famous bands in jazz history. Coltrane, of course, leads on tenor with Red Garland on piano, Paul Chambers on bass, and Art Taylor on drums. Garland had a remarkable intuition for ensemble playing, and could build the mood like a tidal wave. The whole group was really quite telepathic in that sense, a seamlessly cohesive collaboration of creative genius and natural talent. By listening to the whole group interact, you feel Garland's effect which acts as a musical glue that binds the sound. Garland built on his band members' momentum and his initiative behind the piano controlled the rhythmic swell like he was working a throttle. Pay attention: after Coltrane finishes a chorus, you'll sense the band bumping into a higher gear. This is the difference between a good band and one that is merely competent. While soloing, Coltrane really gets out on a limb, pouring out successions of scales in breath length phrases. Garland is right there behind him, ever listening, interplaying with his own lines on the piano, so when Coltrane finishes, the band surges ahead with renewed urgency. But Garland is also a gifted soloist alternating between rich, soulful block chording and arpeggiated explosions of twinkling notes that shower listeners with an inexhaustible pallet of color. Paul Chambers is no slouch either, always fractions ahead of the beat, a guy who liked to cook. His deep tones are an audible heartbeat, the pulse of the group, and he moves like a phantom through the modal inclinations of his band members, adding to the mood and providing the backbone. It's an important album for a jazz listener to appreciate, but it's also just good fun to listen to and that's the important part. It's a record where everything seems to come together and make sense, and every time I listen feels like a special occasion. Take my word for it, try dropping the needle on Soultrane during your next Thanksgiving dinner.

No comments:

Post a Comment